#StopCopCity – Where Environmental and Policing Struggles Collide in the People’s Fight to Protect Life

By Giselle Garcia ’23, Legal Fellow for the Aoki Center for Critical Race and Nation Studies

The intersection of environmental and racial justice against police militarization highlighted in Atlanta’s battle to stop ‘Cop City’ has inspired mass collective action.

What is Cop City?

On June 7, 2021, legislation was introduced to the Atlanta City Council by the City of Atlanta and the Atlanta Police Foundation (APF) to authorize a ground lease of 381 acres in its South River Forest to the APF for the building of an advanced military police training facility. The APF argues the public safety training facility will provide advanced training for law enforcement rooted in harm reduction and includes “antibias training [as well as] LGBTQ community and citizens training.” Despite mass public contestation and over 17 hours of public comment—majority in opposition to the proposal—on September 7, 2021 the Atlanta City Council voted to pass the proposal. The city of Atlanta agreed to foot one third of the construction price and then some: $30 million dollars for construction and $1.2 million a year throughout 30 years for use. The remaining two thirds will be paid for with private funding raised by the Atlanta Police Foundation. The Atlanta Police Foundation (APF) is an independent non-profit which raises private funds and funnels them into the Atlanta Police Department with little transparency and accountability. The APF’s renderings of the facility feature a mock cityscape design for “real world” police training. But the people of Atlanta have expressed opposition to this facility—dubbed Cop City.

Contextualizing the Resistance

Atlanta itself is known as the ‘City in the Forest’ hosting the largest tree canopy of all urban areas in the United States. Its urban tree canopy covers almost 48% of the city and the forest is called “the lungs of Atlanta” because of its major environmental benefits including the yearly removal of 16 million pounds of air pollutants. Additionally, the greenspace reduces storm water runoff from heavy rainfall and reduces Atlanta’s urban heat island effect by 10 degrees. Scientists have warned that the environmental impact of mass deforestation in Atlanta’s forest will be devastating for the city’s residents and organizations have filed a lawsuit under the Environmental Protections Act citing irreparable harm seeking to halt further construction.

It is also important to recognize that the land where Cop City is being erected is afflicted with historical racial violence. It was the ancestral homeland of the Muscogee Creek Tribe who were stewards of the Weelaunee forest before their forced displacement along the Trail of Tears. The forest later operated a slave plantation, and then a prison labor farm in the 1900s. This violent history against people of color in Atlanta continued to evolve through local institutionalized practices like violent policing. Today, Atlanta’s city demographics consist of a 58% racial minority, 48% of which are Black residents. Black Atlantans are disproportionately policed by the Atlanta Police Department and comprise: 84% of people the police use force against, 89% of arrestees, and 90% of people killed by APD between 2013 and 2023. For communities of color, policing does not mean increased safety and to the contrary it poses a threat.

This threat is exponentially increased with the advanced militarization of police departments. Police militarization involves arming local law enforcement agencies with military grade equipment that includes “SWAT teams, paramilitary teams and tactics, military bureaucracies, and militarized ways of understanding crime and criminality in which the default is for officers to see non-officers as potential threats or enemies.” This leads to an increase in use of extreme force in day-to-day interactions with law enforcement.

Policing threatens the psychological and physical well-being of Black and Brown residents through routine surveillance and “act[s] as weapons against communities that speak out on violations of the right to clean air, water, and land.” This is precisely the response seen by law enforcement following the mass mobilizations against Cop City. Not only are Atlantans seeking to stop the devastating environmental impact deforestation will have on a majority Black and Brown city, but they are seeking to stop further police militarization which they have already been statistically disproportionally harmed by.

Violent Repression

Cop City was introduced in the aftermath of the 2020 George Floyd demonstrations which took place across the country and included solidarity protests around the world. Police violence and repression during those mobilizations revealed police forces were “poorly trained, heavily militarized and stunningly unprepared for the possibility that large numbers would surge into the streets.” The plans for Cop city bear all the hallmarks of a space to practice and refine repression. Police repression, far from promoting public safety, is a politically motivated strategy utilized to maintain domination over dissenting populations. As a result, Cop City opponents quickly campaigned to #StopCopCity and argued the mock city would serve to train law enforcement on urban warfare tactics for increased violence inflicted upon minorities and repression of public dissent—as was seen during the 2020 demonstrations.

Residents of Atlanta consistently engaged in public comment and all democratic processes available to them throughout the project’s ratification process in City Council. 1,166 public comments totaling over 17 hours on September 7, 2021, were ignored by city council. 13 hours of public comment on June 5, 2023, were ignored once more. In September of 2023, a coalition of community members collected over 116,000 signatures to put a referendum on the city ballot to give residents an opportunity to be heard. However, the City of Atlanta is awaiting legal resolution regarding what deadline to uphold for signature submissions. If a later filing date is upheld, Mayor Andre Dickens and the City of Atlanta have committed to engage in an abnormal signature verification process for these referendum signatures. This would not be a signature verification process for the actual election vote, but signature verification for the process of introducing this referendum to the ballot—what Mayor Dickens called preventing “risk of petition fraud,” creating yet another hurdle for the people to be heard through the election process. Oral arguments were heard by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in December, 2023 and a decision is currently pending. What is left to do when engaging in our established, so-called democratic processes, have repeatedly failed the public’s effort to save our communities and the environment?

Cop City dissenters have held public demonstrations and repeatedly face an increase in violent police action against protestors. Militarized police repression against Cop City protests led to the murder of Manuel Paez Terán, known as “Tortuguita,” who police shot 14 times while seated with his hands raised. Tortuguita was an indigenous queer and non-binary environmental activist who was deeply a part of the ongoing battle to defend the Weelaunee Forest in Atlanta. Tortuguita’s mother stated “’loved the forest, they meditated there, the forest connected [Tortuguita] with God… I never thought they could die in a meditation position. My heart is destroyed.’” Fellow activists called Tortuguita a “’radiant, joyful, beloved community member who brought an indescribable jubilance to each and every moment of their life and fought tirelessly to honor and protect the sacrament land of the Weelaunee Forest.’”

Even despite recent #StopCopCity actions having committed to engaging in only non-violent direct action—which included planting trees—they were met with mass police presence and violent repression featuring teargas, canines, a tank called ‘The Beast,’ snipers, and flash-bang grenades to ensure the protection of construction property over people’s safety. This militarized action against the public—which can lead to death—is precisely what advocates against Cop City are seeking to end.

Beyond Atlanta

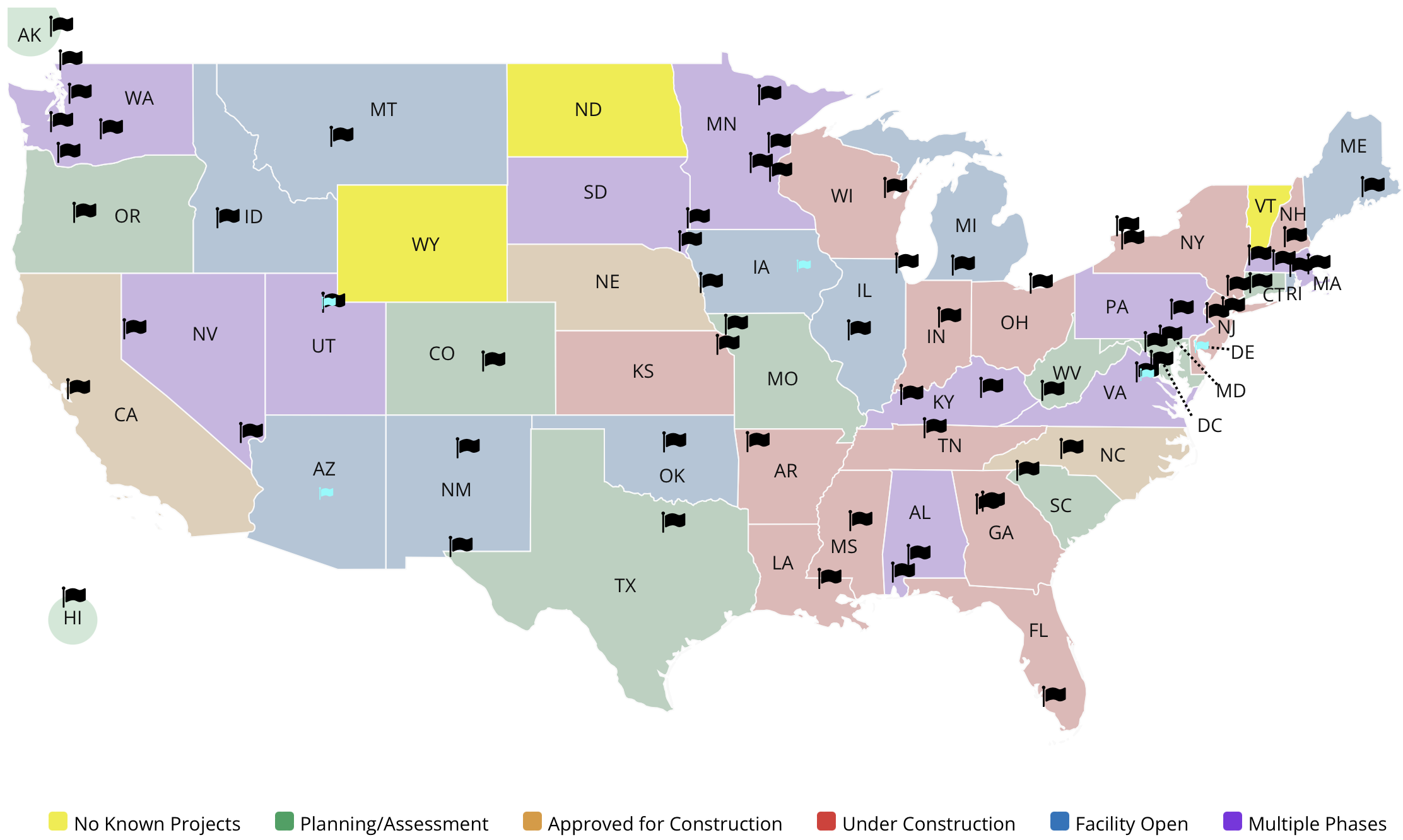

Cop City in Atlanta is not the only mass police militarization training center in progress. Proposals for new police training facilities have sprouted throughout the country from Florida, to Texas, and California. The $43 million project in San Pablo, California, a city of majority Latino and lower-income residents, present the same threats of heavy policing and militarization seen in Atlanta. In fact, only three states in the country do not have similar facilities in the process of being planned or built.

Though most these police training facilities are public construction projects receiving enormous funding from host cities, private donations made for the Atlanta facility reveals a more perverse nature. The Atlanta project is a contract between the City of Atlanta and the Atlanta Police Foundation; however, private corporations funnel donations through the Atlanta Police Foundation without accountability. Such corporations include: the security technology company Motorola Solutions which designed and implemented the Atlanta police surveillance system, insurance companies including Nationwide who is the primary insurer for Cop City, Cox Enterprises a global conglomerate in communications and mass media industries which owned the only major daily newspaper in the metro Atlanta area and has published editorial pieces supporting the project, and more. The list of private donors reveals how deeply connected corporate interests and profits are in lobbying for the project and supporting the hyper-militarization of police.

The fear and effects of militarized policing does not remain a local issue to host cities or just the United States. Both projects in Atlanta and San Pablo have also expressed a commitment to recruit agencies from outside of their cities and Atlanta plans on conducting international outreach to provide training at their facilities. Cop City in Atlanta plans to recruit 43% of trainees from out of state, and while Georgia’s International Law Enforcement Exchange (GILEE) program has already allowed Atlanta officers to train abroad, and other international law enforcement and military agencies will also likely utilize the facility—making the struggle to stop these facilities domestic and international.

#StopCopCity efforts have made clear that social unrest and police militarization are keeping pace together. Ultimately, local governments’ decision to invest in policing and repression training, “rather than community-level interventions that can improve public safety, public health, and climate resilience in tandem,” reveals their priorities. Even if Atlanta government officials chose to proceed with the facility, they could have chosen to build it elsewhere. Yet they actively choose to ignore Atlantans’ plea and expose a majority-minority population to the environmental effects of deforestation. The efforts in Atlanta to protect human and ecological life should inspire us to reflect on how pervasive police militarization has become and just how deeply interconnected our struggles are, whether our commitments rest with environmental or racial justice or opposition to police militarization—they are part of one struggle.